Drug use on school grounds is a growing problem. According to recent reports, 15% of teens in the US report using drugs at school, 60% of educators say student drug use is interfering with their ability to teach, and 50% of students say they’ve seen drugs being used at school.

Recent legislative efforts and state-level initiatives indicate a shift in schools from punitive measures to relationship-centered approaches for students who use drugs. This change is crucial, given the prevalence and inadequacy and harmful effects of current zero-tolerance models leading to negative outcomes like educational disengagement and increased criminality, without effectively deterring drug use. Our current response of pushing students who use drugs out of school are not reducing on-campus drug use, but are worsening their life outcomes.

Evidence suggests that relationship-centered methods and fostering a sense of belonging are more effective in reducing student drug use. However, many students, especially those using drugs, currently feel unsupported by their schools. Reports show that these students who use drugs perceive a higher likelihood of punitive actions rather than receiving help. They also report lower levels of developmental support from adults at school compared to non-users (Heavy AOD Use Among California Students, CHKS 2004).

The need to enforce school policies and norms that drug use is not okay without exclusion is based on the understanding that a lack of school engagement and participation opportunities can lead to dissatisfaction and increased drug use (Fletcher, 2008). Despite these declarations for strengthening relationships as alternatives to punishment, there's a significant gap in providing practical guidance on how to actually foster inclusion and build meaningful relationships with students found to be using drugs.

One reason why these relationships are challenging is that adults working with youth today have been shaped by punitive War on Drugs ideologies that gave rise to no-use and zero-tolerance programs like DARE. These programs and messages perpetuated the belief that we must scare and punish people out of using. In turn, these mindsets have resulted in pervasive biases, stereotypes, and attitudes that foment misunderstanding and mistrust between adults and students (Okonofua, Walton, & Eberhardt, 2016).

Adults working with youth often face their own feelings of anger, confusion, fear, and anxiety when confronted with a child under the influence, particularly in a school setting. This emotional turmoil raises a dilemma: do we react with punishment and shaming or become paralyzed by uncertainty? My previous research found that post-cannabis legalization, the educational response in California has shifted from "just say no" to "just say nothing." While rejecting punitive models, this silence fails to offer an alternative, leading many to inadvertently ignore the issue. Such inaction is detrimental, as it neglects to address substance use during a critical phase of brain development and in an environment essential for learning and growth. This isn't due to a lack of care for the students but rather a lack of understanding of how we adults can connect with students amid our own fears, prejudices, and insecurities.

As a teenager myself who was once using drugs daily to cope with feelings of hopelessness and not belonging, as a researcher and scholar studying the failures and consequences of “Just Say No” and advocating for compassionate messaging and non-punitive-based intervention models in schools, I have lived this dilemma from so many different sides, and I still mess up.

I want to share three stories from my journey on the ground, working to create harm reduction programming in schools and inclusion for students who use drugs. This work led me to the field of social psychology for insights and evidence-based solutions. These three stories have taught me the barriers to forming relationships and potential processes for removing what gets in our way.

I was a naively enthusiastic 22-year-old recent graduate from UC Berkeley. It was my second week working as the “drug coach” at Oakland Tech, a diverse public high school teeming with students from various socioeconomic and racial backgrounds and with different goals. During lunch, I was unsure what to do myself and decided to take a walk around the campus. I was eager to apply a philosophy I learned in my undergraduate program, harm reduction, to reform how schools and adults address teenage drug use. Unlike DARE-style approaches to education and intervention, harm reduction embraces the idea of “meeting teens where they are at”, offering balanced and honest information and solutions beyond mere abstinence. I had the concept right, but how to apply it, I’d soon learn, would be impeded by my anxieties and fears.

As I meandered, I realized my youthful appearance and magenta Jansport backpack gave me a sort of invisibility. Students paid little attention to me; I looked too much like one of them to be staff. This anonymity was an exhilarating feeling, a superpower that allowed me to blend in and observe without disturbing the dynamics.

I eventually found myself behind the buildings, where a group of students was rolling a blunt and getting ready to light it. I froze. As the designated 'Drug Coach,' this was technically my area of concern, but I was unprepared for how to actually respond in real time. My mind raced through the options. Should I intervene and educate them about the risks right on the spot? Should I walk away and passively report them for therapeutic services? My thoughts were a jumble, and I decided this was the moment to introduce myself. As I approached the students and revealed my true identity as staff, I was met with a mix of reactions, ranging from panic to indifference. Two of them began apologizing while stashing the drugs into their backpacks to conceal the scene, and another stood firmly in place, maintaining eye contact with me and saying nothing. I found myself grappling with my own nerves at that moment. I wanted these students to like me, but I also wanted to be effective in my role.

In my uncertainty, I blurted out a judgmental question: "Is this REALLY what you want to be doing?". It came from a place of fear; my own experimentation as a teen with the first-hand consequences made me anxious to remove their drug use as quickly as possible from their lives so they could focus on their growth and health. I meant well, but it was unskillful, and the tone was unintentionally condescending. The connection was lost. I found myself thrust into a position of authority, a role that made them clam up and back away. Any chance for a meaningful relationship had evaporated.

Two lessons were learned here:

1- Connecting authentically and effectively with students is impossible without first addressing and processing my own deeply ingrained biases and fears. If I don't do this, I remain reactive, focusing more on my ego ‘doing something’ than on truly understanding them.

I needed to build trust and relationships first before taking any action. Any effort to promote adherence to policies and norms would be meaningless if this foundation of relationships hadn't been established first.

“All relationships must precede action” without relationship action on any level will only breed conflict. The understanding of relationship is infinitely more important than the search for any plan of action.” - Jiddu Krishnamurti.

I have also experienced some successes in building relationships, which, as a by-product, have effectively reduced on-campus student drug use. These efforts shared some common themes.

I engaged with the whole person, not just the part of the self that used drugs. Our relationship was explicitly committed to helping them develop into who they wanted to become, regardless of their abstinence. Any information shared or expectations I had regarding drug use at school were aligned with helping them meet these high standards, and I constantly reassured them of my belief in their abilities.

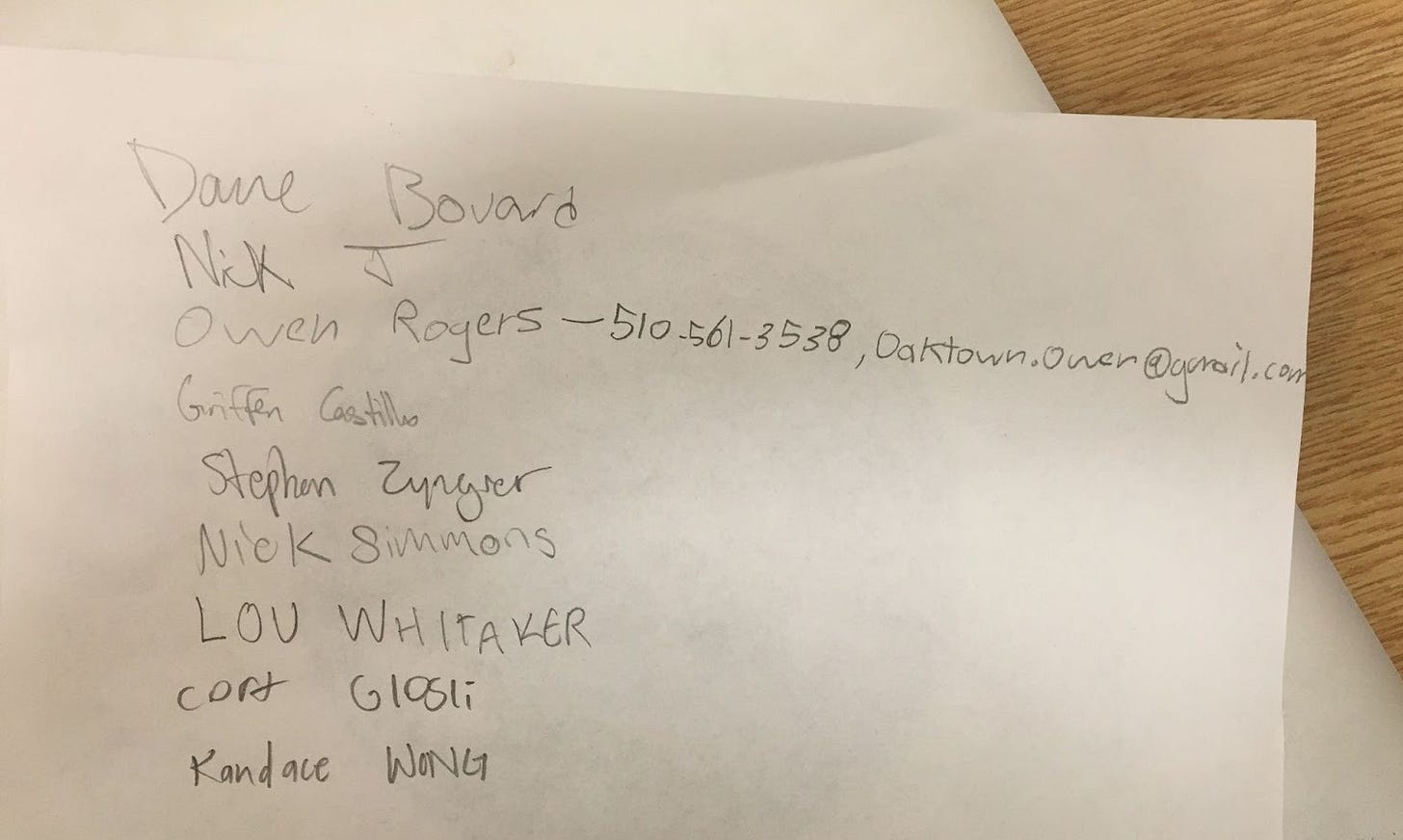

Take Griffin, for example. He was a freshman caught using and selling drugs on campus. Griffin was referred to speak with me, the drug and alcohol life coach, as an alternative to suspension. However, Griffin didn't want to talk about his drug use, or talk to me at all for that matter. Sensing his resistance and mistrust, I shifted the conversation away from his drug use and asked him about his passions and interests. He shared that he enjoyed writing, although he hadn't done much of it lately. I asked if he was close with his English teacher. He told me he used to be but stopped turning in assignments recently and now felt embarrassed to attend class.

We walked together to his English teacher's classroom, where I took the opportunity to re-introduce Griffin as a student who genuinely loved the subject but had been struggling. Through this interaction, both the teacher and I could see Griffin not just as the kid who didn't care, but as a young man who wanted to write and was facing challenges. This allowed us both to engage with the whole person and build on his academic strengths, ultimately encouraging his writing and thereby displacing his focus on smoking weed. This strategy aligns with a wealth of research indicating that when adults nurture students' intrinsic interests and competencies, they can redirect youth paths towards more positive outcomes (PBIS, Walton, 2021).

Despite his initial reluctance, the next week, Griffin texted me asking if we could meet. He was excited to demonstrate his renewed dedication to writing and even brought his journal filled with his musings. We started meeting every week. Over time, Griffin began to open up about his weed-smoking. He talked about how it led to conflicts with his family and negatively affected his coursework. I offered suggestions on ways he could smoke weed that wouldn't interfere with his academic performance or family relationships. Griffin decided to make changes to his use of drugs, with my support as an accountability partner. Over time, he embraced leadership roles within the school, channeled his enhanced writing skills into music production, and founded a band. Griffen’s journey of self-improvement culminated in his graduation, a strong relationship with his family, a sense of contribution to his community, and subsequent college enrollment the following fall.

The above story illustrates that every kid who is struggling with smoking weed is also so much more than that. If we can focus our attention on the vibrancy and complexity of the whole child, water those seeds, and bring in other adults to support their intrinsic strengths and hopes, we can build things within them that sideline their drug use, at least the most risky kinds such as using at school. Griffen never completely stopped using drugs. But he became aware of the harms of his use, stopped dealing, cut back his own use, enforced boundaries on when and where it was appropriate, and made developing his thriving life his priority.

I had another student with whom I was referred to. His name was Stefan, and one day he remarked that he had been benefiting from our non-judgemental and honest discussions about drugs. He felt that many more of his friends would benefit from having a similar outlet, but were falling through the cracks because their absenteeism had left them unidentified by the school as needing support. I asked Stefan what he thought was necessary, and he suggested a drop-in, voluntary, peer-led support group for substance use on campus. I helped him draft the agenda and secured the space. Stefan spread the word among his drug-using circles, and by the second month of school, about a dozen juniors and seniors started to show up to our group.

These students were passionate about discussing drugs and brought a variety of experiences to the conversation. I asked if they could assist me with one of my responsibilities at the school: delivering classroom drug health education to ninth and tenth graders. This sparked excitement, leading us to discuss community values that mattered to us, such as being role models for younger students and sharing knowledge to promote health and safety. They talked about the drugs they wished they had never tried, how nicotine vapes had hooked many of their friends, the effects of smoking weed on their coordination during activities they loved like skateboarding, and how drinking and smoking could easily lead to passing out and vomiting. Despite their own extracurricular activities, the group was united in their desire to dissuade younger students from using drugs or approaching them casually. They wanted to caution them against becoming involved. I would later learn that this aligned with the Lewinian approach to discussion groups, which focuses on subtly influencing social groups to embrace health norms and behaviors through stakeholder engagement.

On the day of the planned 9th and 10th-grade classroom presentations, my students showed up shaven and wearing their finest button-up shirts (a far cry from their dreads and drug rugs), complete with a lesson plan, designated speaker roles, and slides to present. They answered the younger students' questions like professionals and honestly discussed the risks of drug use and their personal challenges in ways I hadn't heard them articulate before. Perhaps they felt more confident because they were seen as role models and leaders of community health, not as outsiders who were looked down upon because of their drug choices.

Treating them as public health leaders led to another unexpected yet welcome shift. After the classroom presentations, I noticed how in our group they would discuss making healthier choices about drug use themselves. Similar to the positive behavior changes via inducing hypocrisy by involving sexually active teens in presenting about the risks of HIV-AIDS, many of my students transitioned to less harmful methods, and some even cut back or quit entirely—all behavior changes I'd hoped for but never explicitly imposed onto them.

With spaces and opportunities that validated their strengths and harnessed their interests, these previously disconnected students were able to engage in activities and roles that they were proud of within the school. They were no longer just drug users who caused problems for other students; but leaders, educators, and role models. In turn, they were more willing to participate and show up.

I would report their attendance to the clerk at the attendance office at the end of the day. After weeks of being unsure if my list was correct, she noted, "These students usually skip all their other classes, but they come to campus at the end of the day to participate in this group.”

In time, they not only showed up to the group but also to all of school because it had become a productive and inclusive place for them.

Even as I began to see positive transformations from my unconventional student leaders, there were times when I felt I was being too risky by giving them so much power and experimenting with this more progressive and compassionate approach. For example, there was a week when I noticed that the younger students joining the group were testing my boundaries by showing up collectively high to our meetings after lunch. Recognizing that everyone faces challenges and that self-medicating was their current solution, I implemented a loving yet firm policy: I made it clear that showing up intoxicated to a group was unacceptable; it hindered their learning and disrespected the effort I invested in preparing sessions meant to be engaging and educational. My investment in their growth warranted their full presence, and I expected them to meet me there to honor our space. Thus, I established a rule—if more than one student came to a session high, I would cancel the group. I explained that although I empathized with their circumstances, the focus was on learning and personal development during school hours. The message wasnt punitive; it served as a reminder of our shared goals—a commitment to growth, learning, and mutual respect. With trust and relationships already established, this policy successfully shifted behavior, with only two isolated incidents of students arriving high for the remainder of the year, and never again as a collective endeavor. This approach to helping them control their use and prevent more risky types of drug use (such as being high at school) aligned with social psychological research on how norms shape behaviors, regulate cravings, and reduce temptations (Kalkstein et al., 2023).

At the end of the school year, a young man approached my group seeking a resource on campus for his drug use. He asked if I remembered him, and I politely apologized for not recalling. He explained that he was one of the students I had scolded during the first week of the previous school year (first story). This moment felt like a full-circle experience for me, showcasing both my professional growth and the importance of fostering a meaningful space where students like him felt seen, cared for, and supported in becoming who they aspired to be. I had confronted my fears and biases and recognized these students as more than just drug users who misbehaved. I created an environment aligned with their values and aspirations. I built a positive relationship and maintained the norm that drug use at school was unacceptable, without ostracizing anyone. Consequently, the student I had previously shut out returned on his own, asking to join.

By the end of the year, the impact was evident anecdotally and statistically. Evaluation reports indicated that 69% of the 78 students on my caseload had self-referred. Research consistently shows that individuals who actively seek assistance for behavioral changes are often more dedicated to the process and typically experience more favorable outcomes than those who are compelled into treatment due to external pressures like school rules or family interventions.

So yes, it's encouraging to see a school shift towards building relationships as an alternative to punishment. But if we are serious about building meaningful relationships with students who use drugs, we need to:

Process our narratives about drugs that may unconsciously drive our reactivity to their behavior rather than centering curiosity and building trust and connection.

See students as More than That. Nurture their strengths and interests and bring in resources to support them so that passion sidelines their drug use. Meet them where they are with the goals they want to set. Listen to their concerns and teach life skills that are aligned with those personal goals.

Engage students who use drugs as public health leaders and role models, providing them a platform to develop a positive identity, regardless of their abstinence. Emulating the behavior of health leaders fosters a positive identity that creates dissonance with their drug-using identity. The need for self-coherence will promote health shifts. The goal is to endorse health behaviors, leading to an attitude shift regarding their health practices.

Establish explicit norms about using drugs at school because we want to uphold the sacredness of the space that is there to help them become. Grounded in high expectations for our students' growth and learning and belief in our capacity to meet those expectations.

Globally, compassionate and public health-oriented responses to drug issues have shown that real change occurs when individuals are connected and reintegrated into the community. This principle holds true in schools as well. By creating opportunities for students to connect with meaningful pursuits and develop into who they aspire to be, regardless of their abstinence, we can foster a sense of belonging, which is a key protective factor for reducing on-campus drug use.

In conclusion, our endeavor to build relationships that reduce drug use in schools is as much about our actions and attitudes as educators as it is about the students themselves. It's about creating a space where every student feels seen as more than just their drug use and feels supported in their journey towards becoming the best version of themselves.